by David Kavanagh

Coming into 2016, journalists and news organisations working in Pakistan find themselves at the centre of an interesting but increasingly dangerous situation.

The Pakistani government has supplied them with a list of 72 outlawed terrorist groups and officially banned reporting on terrorist attacks perpetrated by these groups.

This comes as another measure enforced as part of Pakistan’s ever-escalating struggle against terrorism, which kickstarted when extremists murdered 141 people, including 132 children, at a school in Peshawar in December 2014.

Designed to prevent fear-mongering and the glorification of terrorism within the country, the media ban has resulted in Taliban and other militants targeting journalists over what they perceive to be unfair and imbalanced reporting.

Journalists in Pakistan protest the assassination of colleague Zaman Mehsud by a Taliban gunman, November 2015. Source: Ashraf Ali/ ABC news

While an extreme example, the difficult position the media in Pakistan is currently trapped in – between government regulation and focussed acts of violence – mirrors a larger ethical debate that often comes up in the news media industry: does reporting on the actions of terrorist groups help them get what they want?

Before this question can be answered, it is important to look more closely at what terrorism actually is and what groups employing terrorism tactics hope to achieve.

What is terrorism? What do “terrorists” want?

The academic literature on terrorism and counter-terrorism that vaulted up in popularity post-9/11 is multifaceted and hotly debates varying definitions of terrorism.

Some even suggest that there is no such thing as an inherent terrorist group, and rather only groups that can use particular strategies typically regarded as terrorism.

A revolutionary group staging a coup may, for example, make use of terrorist tactics such as car bombings or assassination, and still not be regarded as a terrorist group because they don’t do it all the time.

To keep it simple, however, prominent scholar Timothy Shanahan describes terrorism as the “strategically indiscriminate harming or threat of harming members of a target group in order to influence the beliefs and/ or emotions of an audience group in ways judged to be conducive to the advancement of some political, religious… [or other] agenda.”

Under this definitional umbrella, there are three primary characteristics of terrorist violence:

- It is politically motivated

- It acts as a form of symbolic communication

- It instrumentalizes its victims

In other words, terrorist acts make use of its victims to send a symbolic and politically motivated message to a target audience. It is not expressly designed just to kill or maim the victims it immediately reaches, but rather to communicate to a larger group.

US journalist Steven Sotloff was beheaded by IS militants on September 2, 2014. Pictured here in Bahrain in 2010. Source: BBC news

The Islamic State beheadings of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff (among others) in 2014, and the devastating attacks in Paris in November last year, were carried out in protest of US and French involvement – primarily in the form of airstrike campaigns – in the ongoing war in Iraq and Syria.

On another level, IS carries out these sorts of violent attacks against the West because the West both symbolically and physically opposes the doctrines of extreme Sharia law it espouses; by their understanding, the two entities cannot co-exist.

Violence, especially when it is heavily reported on, is the best way to make this known.

The news media is a “double-edged sword”

Ubiquitous and ever-growing mass news and social media gives journalists and civilians alike the ability to reach and communicate with billions of people in a matter of seconds.

Before the advent of traditional technologies such as TV and radio, let alone the game-changing entity that is Web 2.0., news and updates about important events in the world were spread by telegraph, paper, or word of mouth.

Today, many studies show that although it might seem like the world is becoming an increasingly violent place – with horrible news emerging daily from at home and from far-off war torn nations like Iraq and Libya – in actuality, it’s becoming more peaceful.

The real difference is that media technologies have made it much easier for us to access and disseminate information than before.

While once a violent group might have had to wait days or weeks for news of their actions and associated political messages to spread, now we can know about them even as they are happening.

Thousands tweeted live updates, for example, as the IS-affiliated gunmen began wreaking havoc throughout the streets of Paris; it was a digital storm the media picked up in mere moments.

In this context, the media acts as a sort-of “double-edged sword”.

Jund Al-Aqsa, a splinter group of the Syrian Al-Nusra Front, lists its official Twitter accounts. Social media is near as much a tool for extremist groups as it is for everyone else. Source: Twitter

Where on one hand, reporting on terrorism ensures news practitioners stay true to their commitment to informing the public about the what, where, how, why, and who relating to ongoing events and issues that could potentially affect their everyday life, on the other hand, they’re playing straight into the hands of “the enemy”.

Without the news media to spread their message, the impact of terrorist violence – spreading fear and division and encouraging sympathisers to join the cause – falters.

It begs the tired cliche: if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? Would terrorist groups continue to commit acts of violence if no-one was going to hear about it?

In the modern arena, the answer to that question may not even matter. With social media constantly brimming with billions of opinions and shares, news now spreads whether the mainstream journalists are involved or not.

That said, established news organisation exist with a level of authority the average joe doesn’t command. If the BBC reports an attack, you can ultimately trust that an attack has happened.

News framing: how the media talks about terrorism matters

Journalists in Pakistan are faced with two absolute options: either they abide by government censorship and stop reporting on terrorism attacks in an effort to shake the hold the Taliban and other groups have on the hearts and minds of the public, or they don’t, and rather continue fulfilling their journalistic duty to tell the truth.

Outside of this severe situation, the answers about what to do when it comes to reporting on terrorism aren’t (thankfully) as black and white.

In the world of professional and ideally ethical journalism, you must consider deeply every word you write or say.

How a journalist writes or says something can determine whether their report will have a positive or negative social outcome.

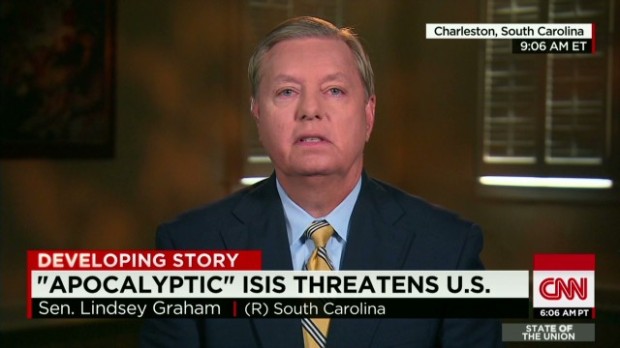

Irresponsible reporting can have dangerous consequences. Source: CNN

This concept of a journalist making decisions in portraying an event – through the language, narrative and images they consciously decide to include (or exclude) in a story – is called news framing.

While more commercial outlets might be tempted to include emotive or exaggerated language in an attempt to win ratings and bring in the revenue, describing an Islamic terrorist as an “evil Muslim” or IS as an “apocalyptic death cult“, for example, ethical reportage should encourage neutral language.

Emotional fear-mongering, after all, is very much what a terrorist organisation would want. IS does what it does because it wants its targets to be afraid.

If the West engages with IS militarily, it is likely because IS coaxed them into it.

Furthermore, language that unnecessarily associates a particular group, such as moderate Muslims, with a particular warped ideology or stereotype, is also greatly discouraged.

Rampant Islamophobia in the post-9/11 world is also something groups like IS encourage. If it can cause its enemies to split internally and fight amongst themselves, half the battle is already won.

As should be becoming evident by now, at the heart of responsible reportage about terrorism should lie fine ethics and consideration about the way the world is framed.

The media is a double-edged sword, but it is up to rational journalists and healthily critical audiences to decide which side to sharpen.

For more of this kind of content, follow Journalytic on Facebook or Twitter