by David Kavanagh

After around two weeks of intensive debate at the COP21 climate talks in Paris, the nearly 200 attendant countries reached consensus and published the final Paris Agreement on December 12.

The unparalleled accord succeeds where the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 failed, uniting the international community in a singular stance against the ever-encroaching threat of climate change and global warming.

“This agreement is differentiated, fair, durable, dynamic, balanced, and legally binding,” said French foreign minister and President of the COP21 talks Laurent Fabius.

While many leaders from around the world expressed a collective sense of cautious optimism about the key elements espoused in the resulting document (which you can read in full here), some experts and activists remain skeptical.

They stress that although the deal is a positive step forward, the real work starts now and a lot more has to be done for it to be effective in mitigating the effects of climate change.

For now, here’s a quick guide to the most important points raised in the agreement.

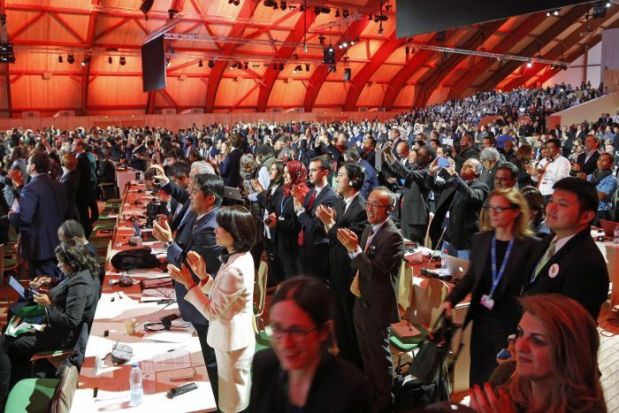

COP21 attendants applaud the adoption of the Paris Agreement after two weeks of intense negotiation. Source: AFP/ Francois Guillot

The 2°C limit:

By adopting the agreement, countries commit to keeping global temperatures at “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

Ultimately, the accord also highlights a more ambitious target of 1.5°C, which vulnerable low-lying island nations say is necessary if they are to survive the dangers of rising sea levels and climate-related disasters at all.

The aim is to achieve this by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases worldwide, with the agreement specifically calling for global emissions to “peak as soon as possible”.

However, experts worry that existing national targets around the world are not enough.

Based on current pledges, global temperatures could rise by about 2.7°C if more ambitious targets aren’t set.

National reviews every 5 years:

In order to ensure countries follow through with their commitment to decrease emissions, the Paris Agreement requires that every nation submit their self-determined emission reduction plans for review every 5 years, starting in 2020.

Each subsequent plan will need to be an improvement on the one before.

While some experts believes this is a great system for checking progress and encouraging ambitious commitment, there is no official requirement that parties must review or upgrade their pledges prior to 2030.

They may do so voluntarily, however.

Financial assistance to developing countries:

Rich and developed countries like the US will be required to provide “climate finance” or financial assistance to poorer countries in order to help them transition and develop using renewable energy.

At least US$100 billion will be contributed every year from 2020 onwards.

While the Paris Agreement doesn’t make any formal distinction between developed and developing nation states, it recognises that rich countries should effectively take the lead and poorer countries should aim to do what they can “over time”.

This is in large part due to the fact that developed and industrialised countries generally emit more greenhouse gases and can also better afford transitions to alternative energy sources than developing states.

As a side note, a significant point of contention during the COP21 debate was the issue of loss and damages, a concept that claims vulnerable countries should be compensated for their losses resulting from climate change by developed countries.

While mention of loss and damages and recognition of the greater vulnerability of developing states made its way into the final document, the requirement of compensation was excluded, reflecting fears put forth by the US that the provision could have been used to sue American companies.

For more, check out The Paris climate agreement at a glance by The Conversation.

For more of this kind of content, follow Journalytic on Facebook or Twitter